Let’s welcome Taliesin – DA representative and low end theoretician with a pair of strong, intriguing mixes floating around. In this extensive post, Tally adjusts his critical lens to explore and scope out a wide range of issues– sampling, copyright, archiving, media, ethics, race, iconoclasm, racism, white privilege, hypocrisy… It’s tremendous, you should just read. – Lamin

*

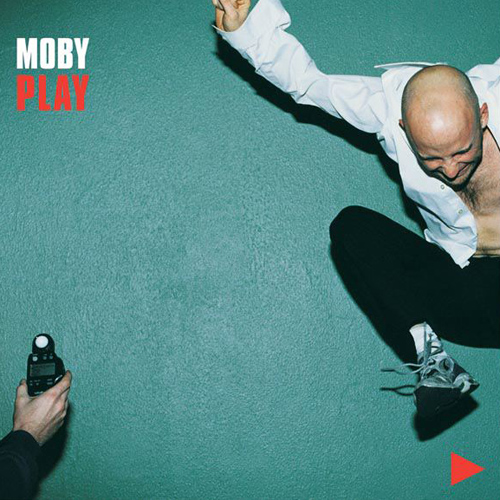

Moby’s 1999 album Play has sold ten million copies worldwide. I bought one myself from Barnes and Noble in the Spring of 2008 to better elucidate some questions I’d been floating about iconoclasm, music and sampling in the age of mechanical/digital reproduction . I hoped to use the album as a focal point for addressing these issues. As a material piece of cultural history Play is nothing extraordinary. Standard jewel case, eight page full color insert, two-color CD label. Photography from British fashion and documentary photographer Corinne Day. Five short essays on fundamentalism, veganism and Christianity. The usual list of production credits and sample clearances.

Copyright, sampling and intellectual property rights ownership are registers fraught with complexity in an age of digital representation and reproduction. As soon as a work of “art†is entirely represented by a series of knowable electrical signals or an infinitely reproducible code, questions of ownership are put into crisis. I have left leaning views regarding information and its inherent desire to be “free,†the laughably (unless you got an RIAA summons) inept response of the record industries to piracy, and my total lack of moral qualms in downloading the work of artists without paying them for the bits of information. What is interesting about Moby’s album Play is not how his work fits into mediascapes of rampant sharing and copyleft issues (although its ad revenue points to new/old models) , but the work itself as a package. By package I mean how the work is presented, its content, and how it is represented by secondary sources that make content out of commentary on, or inclusions of segments of the work itself.

Play appeared as a logical focal point for exploration of sampling and cultural appropriation because it is a work of art authored by a white man that heavily samples the work of black men and women. Sampling in music is about removal, reference, negation and recontextualization. To sample is both a technical act and part of a greater relationship between sound, ownership and authorship. From a technical standpoint sampling is the process of copying sound from one medium and reapplying it to another. Sound is a unique medium because it is ethereal and can only ever can be said to truly exist in the space between the source and the listener. Except for rare instances, sampling never causes the physical destruction of the original sound source. It is for this reason that from a material perspective, sampling does not immediately seem to fit under the auspices of iconoclasm. Musical artworks, however, are

constituted physically in their storage medium and in the sphere of social production. In the relationship between re-contextualized sound and authorship there are iconolastic possibilities traditionally reserved for the analysis of visual arts.

The important questions to ask about Play revolve around the representation of the individual southern rural black voices sampled by Moby and how these voices and any assets they provide to the work as a whole are represented and addressed by what I am calling the “whole package†of the album. On one end of the spectrum appears the possibility of total cultural appropriation in the most negative sense. Moby, white electronic musician, strips black voices of their context, reaps huge material benefits and critical acclaim without acknowledging his cultural theft and the continuation of racist legacies in American music. OR Moby, white electronic musician, brings to light lost recordings of black cultural history, audiences reconsider their historical critical musical timelines, consumers seek out and support sampled artists and their estates bringing a huge influx of funds to ensure the continued support of rural arts. These simplified possible outcomes depend on how Moby and his label understand the meaning of the voices of southern blacks to be recorded, sampled, and released as part of a greater whole, Play , that is coded as white cultural output. Before Play can be placed on this theoretical gradient, a closer inspection of the material reality of the sample sources of the album must be completed.

Play

contains the following cleared (i.e. acknowledged/payed for) samples:

Bessy Jones “Sometimes”

[audio:http://nyc.duttyartz.com/mp3s/BessieJonesSometimes.mp3]

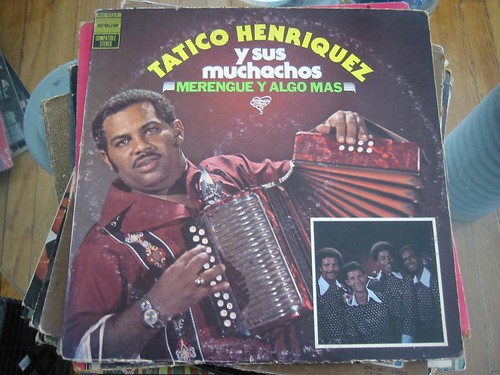

Spoony G and The Treacherous Three “Love Rap”

[audio:http://nyc.duttyartz.com/mp3s/SpoonieGeefeaturingTheTreacherousThreeLoveRap.mp3]

Bill Landford & the Landfordaires “Run on For a Long Time”

[audio:http://nyc.duttyartz.com/mp3s/BillLandfordtheLandfordairesRunOnforaLongTime.mp3]

Vera Hall “Trouble So Hard”

[audio:http://nyc.duttyartz.com/mp3s/VeraHallTroublesoHard.mp3]

Boy Blue “Joe Lee’s Rockâ€

[audio:http://nyc.duttyartz.com/mp3s/BoyBlueJoeLeesRock.mp3]

The black voices that Moby appropriates for Play come almost entirely from the work of folklorist Alan Lomax. Lomax is a white man who is best known for his work traveling rural America and recording traditional American culture. His work yielded more than 5,000 hours of sound recordings, 400,000 feet of motion picture film, and 2,450 videotapes. Lomax was (according to the organization that bears his name) “A believer in democracy for all local and ethnic cultures and their right to be represented equally in the media and the schools – a principle he called ‘cultural equity.”

The mission of the Association for Cultural Equity he founded is stated on their website as follows:

Alan Lomax hoped that cultural equity, the right of every culture to express and develop its distinctive heritage, would become one of the fundamental principles of human rights. ACE’s mission is to facilitate cultural equity through cultural feedback, the lifelong goal that inspired Alan Lomax’s career and for which the Library of Congress called him a Living Legend. Cultural feedback is an approach to research and public use that provides equity for the people whose music and oral traditions were until recently unrecorded and unrecognized. Cultural equity is the end result of collecting, archiving, repatriating and revitalizing the full range and diversity of the expressive traditions of the world’s people — stories, music, dance, cooking, costume. ACE’s mission is realized through a configuration of innovative projects that creatively use and expand upon Alan Lomax’s collected works and research on music and other forms of expressive culture including:

* The digitization of and free

access to a vast majority of Alan Lomax’s musical and scholarly files in an evolving website which is open to the public.

*The commercial distribution

of sound and video recordings from the Lomax collection linked to the payment of royalties to the original performers or their descendants.

*The repatriation of media

collections to libraries established in the areas where they were collected.

* A pilot project for cultural

feedback based on Lomax’s work in the Caribbean.

* A revisited performance style

research paradigm testing old and new hypotheses and including new statistical

techniques and breakthroughs in evolutionary anthropology.

While Moby shouts out “The Lomaxes†(Allen’s father recorded and brought (mostly black) cowboy songs among other things into American lore) in his liner notes, it’s questionable whether Moby really honors

the tenants of cultural equity (saving deep explorations of Lomax’s project for a later date) in his presentation of the disembodied black voices on/in Play.

The initial recontextualization of black cultural experience, by Lomax, performs a dual role of preservation and destruction. By recording traditional American folksongs, Lomax ensures that they are not lost to time. This is a function that recording always carries. Recording however, always misrepresents, or at least alters, that which it claims or can appear to be an exact reproduction of. The recorded vibrations of air pressure that we discuss as sound is always situated in a specific cultural, historical, geographical, temporal moment that is entirely lost no matter how much documentation a folklorist or other archivist attempts to complete. In this way the work of preservation comes into

question. Is there something wrong if gorgeous and haunting recordings of southern gospel traditionals are consumed as Play delivers them by an affluent audience without reflection (what ever the fuck that means) on the complex and violent history of slavery, oppression and racism from which they emerge? I believe there is.

When important parts of history are stripped from culture and expropriated for pure aesthetic value something valuable and essential is lost. The Lomax archives are important because they also spur interest in rediscovering a history that is often white washed in American public education. Because the

media is already awash with racial caricatures and rehashed minstrelsy, preservationists should not be the prime targets of criticisms about media representation. The power of these recordings speaks strongly about their historical position, and I imagine for many inspire a deep exploration of

American identity and history.

Moby’s work provides a different type of mediation however, from that of Allen Lomax and other archivists. While Lomax did indeed choose when and what to record, it is the really the technology of the

recording apparatus, in Lomax’s case 1/8†tape, that provides the essential link between the original sound and the listener. Moby’s mediation, the loading of an entire song, a complete hymnal, into ProTools (or equivalent DAW) and violently puncturing it through editing is a different kind of act. I agree with departed ethnomusicologist and cultural historian Tim Haslett when he

writes:

White Americans are actually terrified of Black

music’s aesthetic, political, and affective power. It is as if they understand

that for Black people, including artists, music is not a recreational activity,

it is a way of life and often a means of survival. It has to arrive via a white

mediator in order to be absorbed without damaging whiteness. This mediation

process is evident in the… success of the electronic artist, Moby.

The enormous power of Moby’s mediation is made clear in the commercial success of the licensing of the album’s songs for commercial purposes. The tracks have been licensed hundreds of times. Reviewers

of the album describe it as being “visceralâ€, “a spiritual epiphany,”

and having “uniquely affecting soul.â€

Somehow Moby has tamed the crude and deep emotions of the Southern negro and created a music with all of the potent signifiers of hip (synth pads!!! safe minorities !!! bass beats!!!) and none of the burden of the lived experience of black folk. Can you imagine hundreds of advertisements that feature painfully honest and striped imagery of racism, rural poverty, death and god? Yet the potent themes are exactly what the vocals manage to do (for some) once run through and controlled by Moby’s studio. Once these words enter into the editing environment they loose their original context and retain only a vague hint of soulfulness, genuine lived experience, and foreign danger. These attributes provide an erotic thrill to Moby and his global audience when they are allowed intimate access to, and total control over the lives of blacks. When the harsh realities of the antebellum south that refuse aestheticization and corporate branding (lynching, prison slavery, endemic poverty, jim crow, and the limitation at every possible

turn of life success chance possibilities for blacks and natives…) emerge as the clear underpinning of the “soul†that is so beloved by white audiences, escape always and must be a mere eject button away. Play provides whites with the ability to imagine occupying the space of the other, the church hall, the front stoop, the chain gang without even breaking a sweat, much less addressing the continued legacy of slavery in America.

Looking back at Moby’s earlier career choices, Play appears on a continuum of artistic decisions that

consistently utilize reduced notions of blackness for emotional effect. An early 90’s track under his pseudonym Barrcuda “Party Time” also utilizes disembodied black voices. A black male voice shouts at various intervals “Its Party Time!†while a gospel choir moans “Ahhhhs†in the background. Another pseudonym of Moby’s, Voodoo Child, is also problematic. Evoking the tribal and crazy dangerous world of Voodoo practice (or Jimi), Voodoo Child is of course merely Richard Hall, middle class white man raised in Darien, Connecticut.

It appears that Moby is also aware of this position of privelege. In an interview he says, “The only way dance music culture has been accepted in the U.S. is when white people have done it. I’m white, so I can’t really complain, but the roots of dance music are gay, black and Latino. It’s weird that I’ve gotten a lot of attention when there are so many gay, black and Latino house producers from New York who never got any attention.”

Why then doesn’t Moby focus more the debt he owes to black artists, both those he samples and those whose legacy of electronic music he mines? I think what borders on iconoclasm may lie in the way samples are addressed in the total package of Play. There are no links to the sample sources on his website or that of his label. The liner notes don’t mention the cd comps (where the samples come from maybe these already are troubled), merely the artists and track titles. The artists whose voices he employs, already magnetically bound on tape are divested of all agency, even the freedom to sing the entirety of a song. Play doesn’t qualify as inconclastic because it didn’t break boundaries or cause a sensation, it merely continues plodding along appropriating and aesthetisizing the experience of black Americans, polishing them up and selling them off without looking back.